On the 16th January this year the world became a little greyer as David Lynch shuffled off of this plane, presumably into the antechamber of some much odder place with a penchant for red velvet curtains.

Like many people of my age, my first encounter with David Lynch was Twin Peaks flickering onto the small screen in the early nineties. It felt like another world, indeed it was another world and one far stranger than we could imagine. One that looked as cosy and familiar as an apple pie on the surface but was far weirder and stranger and ultimately more disturbing underneath. One where the apple had been allowed to wither and rot away below the surface.

The ironic thing is that when Lynch was interviewed he came over as the opposite. Mel Brook’s description of him as “Jimmy Stweart from Mars” is apt, reflecting his down to earth everyman persona of someone who was unfailingly polite and was never heard to swear, a genuine boy scout (of which he was immensely proud) whose charming demeanour disarmed you even as he was discussing whatever strangeness he was working on.

And that pretty much describes most of his output over the years, charming and kooky on the surface but troubling underneath.

But Lynch was far more than that. Lynch was above all an artist interested in exploring film as a medium of dreams, albeit ones that often resembled nightmares, of turning the traditional narrative on its head to create stories and loops within stories and loops, a puzzle knot to be deciphered. Even his most conventional seeming films reflect this, images recur throughout and across films almost establishing a shared world between his works of shared memories and often shared lives.

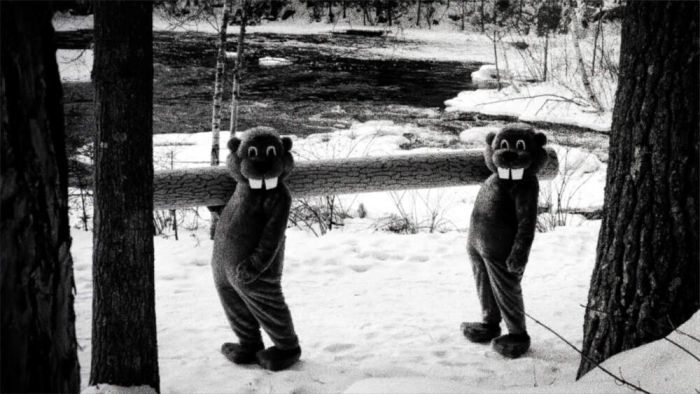

His films covered a variety of genres, surrealist horror, Victorian melodrama, sci-fi epic, comedy, but more often than not mysteries which allowed him to explore the dreamlike vistas he became known for. To me his three best works explore this most, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks. The first two explore his recurring theme of “A woman in trouble”, blurring the lines between the victim and femme fatale in each case to create a level of discomfort Inn the audience. The latter was something else, starting as a mystery attached to a soap opera, but in the latter series released twenty-five years after the original it again morphed into something else. Episode Eight in particular may be one of the most experimental pieces of television ever released, a meditation on evil loosely formed around the narrative of the Trinity Test Site that allows for a deeper exploration of what Twin Peaks is about.

Lynch was also one of the great directors of women. Many of his films revolved around the premise of “A woman in trouble”, but in each case that only told half the story and, there was meat to those roles. Lynch trusted his women to carry his films rather than reducing them to the supporting role. It’s difficult to stress how increasingly uncommon this is, especially within Hollywood. Lynch even poked fun at this, the audition scene from Mulholland Drive is a masterclass in taking apart the traditional female role within film, stripping it back and creating another narrative within the wider narrative, one that questions how Hollywood treats women.

His soundscapes were also integral, often discordant hellscapes mixed with pop bubblegum. Dean Stockwell miming to Roy Orbison is an image that is difficult to forget as is the clicks and hisses of hundred of beetles as they writhe in a severed ear.

So goodbye Mr. Lynch and thank you for invading our dreams over the last fifty years with your dark and troubling own.